Hong Kong case studies: Part 2

Lam Tsuen River

Introduction

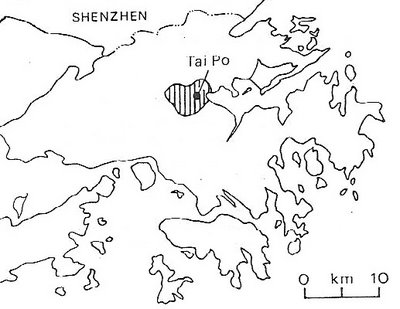

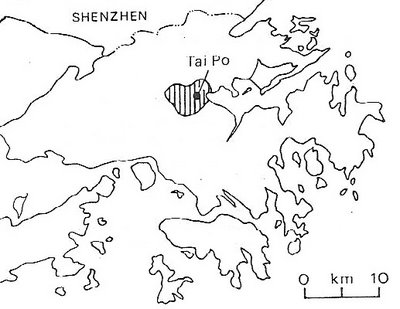

The Lam Tsuen River, in the New Territories, is about 9 km in length. It has a broadly circular drainage basin with an area of approximately 18.6 sq km. Its source is on the slopes of Tai Mo Shan (957 m) and has the highest point in the watershed is at about 800 m.

The upper course of the river flows over mainly volcanic rocks, with a series of waterfalls where the resistance of the rock varies. The vegetation is shrubland with forested ravines (deep narrow gorges with steep sides). The river is actively downcutting, and flows in a narrow V-shaped valley. Rapid weathering and landslips help to maintain the steepness of the valley sides. Given the steepness of the slopes, the river meanders little in its upper course and the headwater streams are therefore relatively straight.

In its middle course, the Lam Tsuen flows across an alluvial valley floor, which increases from a width of about 0.5 km to about 1.2 km. In this stage, the river follows a series of wide meanders. The surrounding floodplain is now used for intensive market gardening, and the area is known for the production of flowers, peach blossom trees (which signifies longevity), tangerines (which signifies 'fruitful' marriages) etc., for the Chinese New Year Festival.

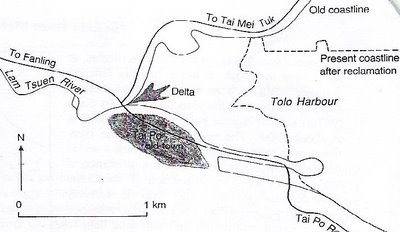

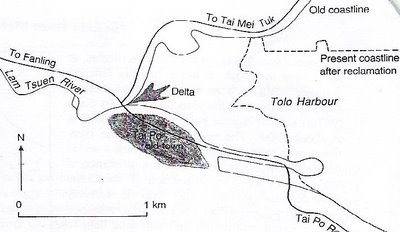

Downstream of this point, in its lower course, the river can no longer be considered as natural. Until the construction of Tai Po New Town, the river entered the sea via a delta. This developed as the river's load was deposited in the sheltered waters of Tolo Harbour. Today, the river is impounded at Tai Po Au by an inflatable barrage and water is pumped from the river to the Plover Cove Reservoir. Only a small fraction of the river's discharge continues to flow beyond this point. Downstream of this, large-scale reclamation for the New Town has meant that the river's course is now entirely channelised and the original delta is now gone.

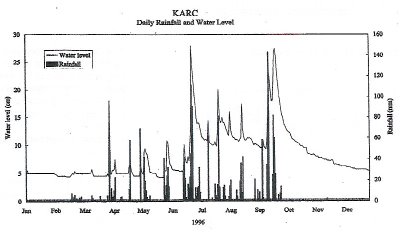

River's regime

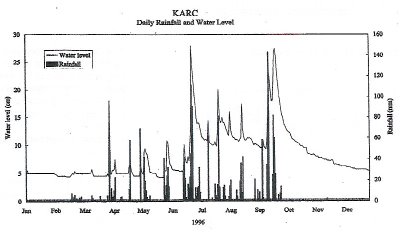

Hong Kong has a seasonal monsoon climate. Average annual rainfall is approximately 2000 mm/year and much of this arrives during the summer wet season from May to September. At this time of year, the discharge is high and flood peaks as sudden convectional storms and typhoons bring intense rainfall.

The steep slopes, impermeable rocks, small catchment area and thin soils encourage rapid run-off from the upper part of the basin. In addition, only a moderate amount of rain will generate significant increase in discharge, e.g. in August, as the ground is already close to saturated due to the wet antecedent condtions.

In contrast, the discharge is much lower in the winder dry season.

Managing river procceses

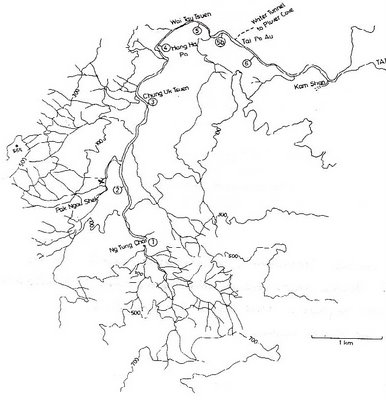

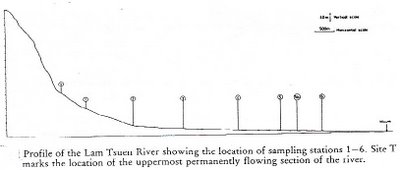

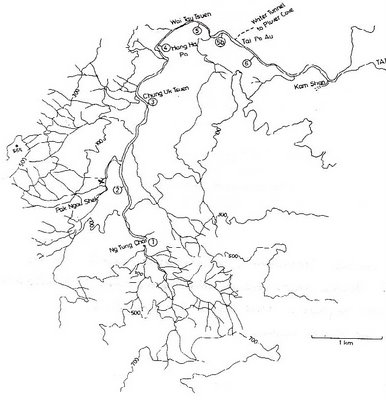

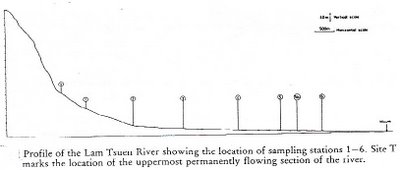

On the map and long profile above, the numbers indicate sampling sites that will be used to refer to specific locations along the river and its tributaries.

In the headwaters (1), the channel is natural, with water flowing over a rocky bed. The large rocks on the bed are only moved under very high discharge. The flow is turbulent due to the nature of the bed. At (X), the stream has been channelised and now flows between concrete walls, over a series of steps. This was done in the early 1990's prior to major roadworks in the area. The flow of the river is now controlled in this section so that it will not meander and erode the newly widened road.

At (2) and (3), the channel is much wider and the bedload is smaller, decreasing from small boulders to coarse sands. Between these two sites, the flow gradually becomes less turbulent. The channel throughout this section is largely natural, but gabions have been used to strengthen the banks around structures such as bridges, especially where undercutting on the outer bend of a meander would be likely to occur.

Below site (3), the river meanders gently across the floodplain. Downstream of this point the river is almost totally channelised to:

Just upstream of the waterworks at Tai Po Au, at site (5), the river flows in a small flume at the base of a very wide channel.. At (5a), the river is impounded and so it appears to be wide and very slow flowing.

Beyond this point, the river has been totally channelised since the 1970's and the construction of Tai Po New Town. This was necessary due to:

A bit off topic, but the cycling path from Sha Tin to the Plover Cove Reservoir in Tai Po is near divine. The track is easy and not very occupied if you go on weekdays. Approximately 20 kilometres - one way, 40 kilometres - return trip.

Read Part 1 here.

Introduction

The Lam Tsuen River, in the New Territories, is about 9 km in length. It has a broadly circular drainage basin with an area of approximately 18.6 sq km. Its source is on the slopes of Tai Mo Shan (957 m) and has the highest point in the watershed is at about 800 m.

The upper course of the river flows over mainly volcanic rocks, with a series of waterfalls where the resistance of the rock varies. The vegetation is shrubland with forested ravines (deep narrow gorges with steep sides). The river is actively downcutting, and flows in a narrow V-shaped valley. Rapid weathering and landslips help to maintain the steepness of the valley sides. Given the steepness of the slopes, the river meanders little in its upper course and the headwater streams are therefore relatively straight.

In its middle course, the Lam Tsuen flows across an alluvial valley floor, which increases from a width of about 0.5 km to about 1.2 km. In this stage, the river follows a series of wide meanders. The surrounding floodplain is now used for intensive market gardening, and the area is known for the production of flowers, peach blossom trees (which signifies longevity), tangerines (which signifies 'fruitful' marriages) etc., for the Chinese New Year Festival.

Peach blossom trees, lucky charms, and tangerines

Downstream of this point, in its lower course, the river can no longer be considered as natural. Until the construction of Tai Po New Town, the river entered the sea via a delta. This developed as the river's load was deposited in the sheltered waters of Tolo Harbour. Today, the river is impounded at Tai Po Au by an inflatable barrage and water is pumped from the river to the Plover Cove Reservoir. Only a small fraction of the river's discharge continues to flow beyond this point. Downstream of this, large-scale reclamation for the New Town has meant that the river's course is now entirely channelised and the original delta is now gone.

River's regime

Hong Kong has a seasonal monsoon climate. Average annual rainfall is approximately 2000 mm/year and much of this arrives during the summer wet season from May to September. At this time of year, the discharge is high and flood peaks as sudden convectional storms and typhoons bring intense rainfall.

The steep slopes, impermeable rocks, small catchment area and thin soils encourage rapid run-off from the upper part of the basin. In addition, only a moderate amount of rain will generate significant increase in discharge, e.g. in August, as the ground is already close to saturated due to the wet antecedent condtions.

In contrast, the discharge is much lower in the winder dry season.

Managing river procceses

On the map and long profile above, the numbers indicate sampling sites that will be used to refer to specific locations along the river and its tributaries.

In the headwaters (1), the channel is natural, with water flowing over a rocky bed. The large rocks on the bed are only moved under very high discharge. The flow is turbulent due to the nature of the bed. At (X), the stream has been channelised and now flows between concrete walls, over a series of steps. This was done in the early 1990's prior to major roadworks in the area. The flow of the river is now controlled in this section so that it will not meander and erode the newly widened road.

At (2) and (3), the channel is much wider and the bedload is smaller, decreasing from small boulders to coarse sands. Between these two sites, the flow gradually becomes less turbulent. The channel throughout this section is largely natural, but gabions have been used to strengthen the banks around structures such as bridges, especially where undercutting on the outer bend of a meander would be likely to occur.

Below site (3), the river meanders gently across the floodplain. Downstream of this point the river is almost totally channelised to:

- Prevent loss of valuable farmland due to river erosion, and

- Prevent flooding during period of high discharge

Just upstream of the waterworks at Tai Po Au, at site (5), the river flows in a small flume at the base of a very wide channel.. At (5a), the river is impounded and so it appears to be wide and very slow flowing.

Beyond this point, the river has been totally channelised since the 1970's and the construction of Tai Po New Town. This was necessary due to:

- Prevent flooding of the urban area, and

- Transfer the river over the newly reclaimed land without eroding it

Tai Po New Town

Plover Cove Reservoir: the largest in Hong Kong in terms of area; second largest in terms of volume, after High Island Reservoir, which stores water from China

A bit off topic, but the cycling path from Sha Tin to the Plover Cove Reservoir in Tai Po is near divine. The track is easy and not very occupied if you go on weekdays. Approximately 20 kilometres - one way, 40 kilometres - return trip.

Cycle path

Read Part 1 here.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home